Martin Tengler, Tokyo-based lead hydrogen analyst for BloombergNEF, likes to talk about how we’re on the cusp of at least the fourth pro-hydrogen near-frenzy since 1974. That’s the year Road & Track touted “Hydrogen: New & Clean Fuel for the Future” on its March cover. They probably didn’t mean more than 45 years in the future.

The second frenzy came in 2005, when the CEO of Ballard Power Systems, maker of fuel cells, said they’d be selling between 200,000 and 500,000 a year to auto manufacturers by 2010. They did not hit that mark.

And then there was 2009, when multiple auto manufacturers signed a joint letter of intent that by 2014, they would be selling hundreds of thousands of hydrogen-powered cars. That didn’t happen, either.

But this next near-frenzy might be different, Tengler believes. Just in the past year, forecast growth, or at least interest, in hydrogen power has grown beyond even recent predictions. While most automakers have announced ambitious electrification plans pegged to plug-in vehicles, Honda recently made sure to include hydrogen-fuel-cell vehicles in its goal to phase out gasoline engines in North America by 2040. Daimler Trucks and Volvo have partnered in Europe to try to help cut costs and make hydrogen make financial sense for long-haul trucking.

Why is Tengler optimistic now? Especially as California, the one place in the U.S. with hydrogen infrastructure, continues to wrestle with supply in the face of even modest demand. Because costs will begin to decrease considerably for hydrogen production, and not just dirty “gray” hydrogen produced by, say, fossil fuels or coal-generated electricity, but of non-polluting green hydrogen.

Tengler thinks those costs could plunge by 85 percent by 2050. Meanwhile, no one is predicting gasoline will decline by 85 percent by, well, ever.

Costs could dip below $1 per kilogram of hydrogen by then, compared to an average cost of $16.51 per kilogram in 2019. The hydrogen-powered Toyota Mirai averages about 73 miles per kilogram, according to the EPA.

Interestingly, though, this latest hydrogen frenzy has little to do with cars. In fact, Tengler said, “Hydrogen may not be the best fuel for cars.” Compared to electricity, that is.

What has Tengler and his forecasting team excited about hydrogen is its industrial future, making steel, plastic, and cement, which it does now, and powering airplanes, ships and trains, which it doesn’t. At the head of the cost-reduction predictions are, Tengler said, solar PV. Solar photovoltaic, or PV, combines words for light (photo) and electricity (voltaic). Solar PV is how solar converts sunlight into electricity, and the process can also be used to create hydrogen fuel. “Falling costs of solar PV are the key driver,” Tengler said, behind his enthusiasm for hydrogen, which reflects his enthusiasm for solar.

Also, his enthusiasm for China. Most of the electrolyzers, which make hydrogen, are made in China, and the vast majority of solar equipment is made in China, and the overwhelming percentages are expected to grow.

“Such low renewable hydrogen costs could completely rewrite the energy map,” Tengler said. “It shows that in the future, at least 33 percent of the world economy could be powered by clean energy for not a cent more than it pays for fossil fuels. But the technology will require continued government support to get there—we are at the high part of the cost curve now, and policy-supported investment is needed to get to the low part.”

So solar is one potential solution to improving the hydrogen supply. Two others could make their way to California by the end of the year.

WAYS2H: Garbage + Thermochemical Process = Hydrogen

Jean-Louis Kindler, co-founder and CEO of Ways2H doesn’t yet practice what he preaches. “I drive a gas guzzler,” he said. “I love my gas guzzler.” Sure, he’d like to drive something powered by hydrogen to the nearest Trader Joe’s, but the available inventory of hydrogen-powered vehicles doesn’t much appeal to enthusiasts of large or sporty vehicles, but Kindler thinks it’s coming.

And by then, he’ll be able to pump processed garbage into its tank.

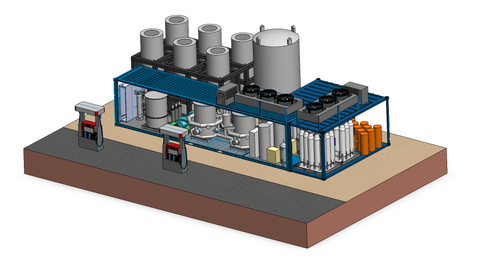

Kindler’s company plans to build relatively small hydrogen refineries near garbage dumps, separate out the metal and glass, and use the rest—from milk cartons to cat litter to what is described picturesquely as “sludge”—to make “blue” hydrogen.

About 90 percent of today’s hydrogen is “gray,” made with electricity or fossil fuels. The hydrogen is then loaded into tube trailers towed by tractor-trailers and delivered to refilling stations, the majority of which are in California; that delivery is the most expensive part of the per-kilo price. As clean energies go, blue hydrogen is better. (“Green” hydrogen, the type that could be produced by solar, is the Holy Grail.)

Kindler’s refineries use a chemical process to generate the necessary heat—not electricity or petroleum—to 1200-1300 degrees Fahrenheit—in an oxygen-free atmosphere. “Entirely plausible,” to make hydrogen from garbage, said BloombergNEF’s Tengler. “It’s being done here in Japan.”

Kindler’s first Ways2H refinery is coming from Japan, three containers that will go on the boat in June, and could be producing hydrogen from garbage in California by the end of the year. Where in California? He isn’t ready to say. Larger systems would be built in place, but Kindler wanted to start with a smaller one to illustrate its portability. It will be a modest operation at first, taking garbage from the community where its located, then returning the hydrogen to the city to power.

The standard-sized Ways2H system “processes 24 tons of waste per day, for a 1- to 1.5-ton hydrogen yield,” said Kindler, enough to fill the tanks of 200 to 300 passenger vehicles.

“Did you know there are 30,000 hydrogen-powered forklifts in America?” he said. We did not. But it makes sense—no pollution inside the warehouse, and no three to four-hour downtime as they recharge their batteries.

Kindler said the refineries are scalable, and can be made much larger to produce commercial hydrogen that can be marketed. A major customer? The long-haul trucking industry, which is hard at work on hydrogen-powered vehicles.

And, for Kindler, maybe a big, comfortable hydrogen guzzler, as soon as somebody makes one.

POWERTAP: Making hydrogen on-site at gas stations.

If you watched the IndyCar season opener from Barber Motorsports Park in Alabama on April 18, maybe you saw some Andretti Autosport crewmen with “PowerTap” on the back of their uniforms. It was a quiet coming-out for a company that says it plans to have 500 hydrogen refueling stations open in the next few years, starting with 29 in California, at existing stations owned by racer-businessmen Mario and Michael Andretti.

Unlike current stations, PowerTap plans to construct small buildings at the existing stations that will house hydrogen production equipment. It will use natural gas and city water to produce blue hydrogen, capturing and storing leftover carbon.

It’s a conventional method—”The technology dates back a hundred years,” Tengler said, and China is cranking out inexpensive electrolyzers at an impressive rate, so the buy-in isn’t that expensive.

But like Ways2H’s Kindler, PowerTap CEO Raghu Kilambi sees a much more immediate path to profit through the 18-wheeler and medium-sized truck market, rather than through automobiles. Yes, he’s aware of battery-powered semis like the proposed Tesla version, “but I don’t believe it’s commercially viable now.” The size and weight of the necessary batteries, the length of time to charge them, the infrastructure required to recharge semi-trucks—hydrogen is ready now, as soon as truckers have a place to buy it. Toyota is likely to be the first on the road with a hydrogen-powered heavy truck, unless Nikola can get its house in order.

Plus, all you have to do to sell a new type of truck is to be sure it makes business sense. “Cars are often emotional purchases,” Kilambi said. “People don’t buy Ferraris because they generate income. Trucking companies will buy what they need to make a profit.” The ability to locate hydrogen production and refueling stations all over the country is a major boon for the hydrogen-powered trucking initiative—no need to transport hydrogen to far-flung places through pipelines, rail or trucking.

Kilambi also said that his stations can produce a kilo of hydrogen for several dollars. If he can sell it for, say, $8 a kilogram, it would nearly halve the price of current hydrogen outlets.

What’s making PowerTap possible is just what Tengler said would be necessary—”policy-supported investment”—or in other words, government money. And California’s generous carbon credit system. At one point, Kilambi said, you got carbon credits for what you sold. But now, you can get carbon credits for the infrastructure as soon as you have something to sell, and that plays a big part in PowerTap’s financial strategy. Carbon credits are a tradable asset, and their value, under the Biden administration, is likely to blossom, and may spread to other states, Kilambi hopes.

In a chicken-or-egg scenario, it appears the egg is being financed by the government before they sell any chickens. PowerTap will build the stations with largely private capital, and once they are built, they’ll collect enough carbon credits to tide them over until the hydrogen market catches up to the new supply.

On paper, it works. We could see how well it works in the real world before the end of the year.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Source link