From the July 1995 issue of Car and Driver.

Of all the mixed blessings and curses of my life, I put motorhomes at the top of the list. —Charles Kuralt

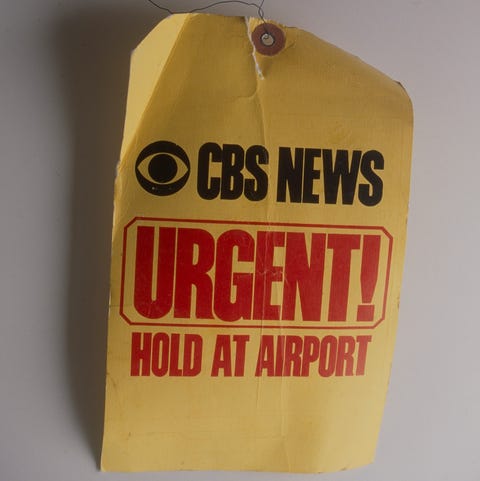

The TWA tag on the faux leather flight bag says: “Property Charles Kuralt, 34 Bank Street, NY, NY, 10014.” Inside the bag, I find: one khaki safari shirt, one pair of slacks with suspenders, one woolen pullover from Saks Fifth Avenue (size XL), one pair of Wallabees with felt insole liners (size 12), one pair of long underwear (bottoms only), two pairs of gloves, one knit cap, a typed list of CBS affiliates, a bottle of Murine, an “Ear Wax Removal System,” plus a booklet intended to accompany a Smith Corona 8000 typewriter. Here is its title: Rules for Safe Operation.

Not far from Kuralt’s bag is another book: Jack London’s The Call of the Wild. It was checked out of a library seven years ago, when Kuralt was last aboard this ratty 1973 FMC 2900R motorhome, videotaping segments for the television show On the Road. The motorhome was parked in 1988, but its contents were left undisturbed in case the CBS team opted to return. Criminal proceedings may now attend the library book’s long overdue return.

Rifling through Charles Kuralt’s personal effects, I felt like a voyeur, a scopophiliac. But I had to find out. Kuralt, now 60, began his career as a correspondent in 1957. He has never stopped traveling, not even after his retirement from CBS a year ago. Just what, precisely, does a man pack if he has no fixed address and expects to roam America randomly in motorhomes for 20 consecutive years?

My curiosity was sated courtesy of subscriber and BMW-phile Tom Goodman, who is a CBS vice-president. Goodman asked if Car and Driver wanted to drive Kuralt’s On the Road coach from Chicago (where it was last parked) to Dearborn, Michigan, where the white behemoth would be put to perpetual rest in the Henry Ford Museum. The trip would be the vehicle’s last drum roll through small-town America—this after Kuralt, cameraman Isadore “Izzy” Bleckman, and soundman Larry Giarmeschi had logged more than one million motorhome miles throughout 48 states. In total, the threesome recorded some 500 On the Road TV segments, many recently edited into 60 half-hour shows for the Travel Channel.

As it turns out, Kuralt and his CBS colleagues used up six motorhomes: two Travcos, two Cortezes, one Revcon, and the FMC shown here. “The first bus—we never called them motorhomes—was the Travco acquired in the fall of 1967,” says Kuralt. “It didn’t even belong to CBS. We rented it from the National Geographic Society.

“[It] was a Dodge truck chassis perilously supporting a fiberglass body—a pink box that swayed alarmingly when underway. The second [Travco] was purchased with CBS’s money, and we painted it white.”

Cameraman “Izzy” Bleckman, now 59, the man who unwittingly became the team’s mechanic, chose the third bus. It was a Cortez, and Izzy was usually at the wheel. He grew a mustache to emulate his hero, British F1 driver Graham Hill. “Izzy owned sports cars,” says Kuralt, “and he was a good driver, the Juan Manuel Fangio of motorhomes. It was okay with me that he usually drove because it left me to sit at the bus’s desk and think.”

The trio’s love/hate affair with the Cortez lasted nearly a decade, although the “hate” component of the equation eventually achieved dominance. “Its metal body was way too heavy for the flimsy chassis and suspension,” recalls Kuralt in his book, A Life on the Road. “What was a bump in the road to others was probably a blowout or broken wheel to us. In California redwood country one Sunday, I glanced into the mirror to notice that we were trailing smoke and fire . . . the rear wheel bearings had welded themselves to the rear axles.”

After the second Cortez attained terminal mechanical decrepitude, Kuralt discovered “that the company had gone broke and was blessedly unable to provide a third. We bought a brand-new Revcon,” Kuralt recalls, “an elegantly appointed product of California. This was my idea. I liked the thick carpet.”

Bleckman regarded the Revcon with fear and loathing. “You know, if Charles were a woman, he’d be pregnant all the time,” he says. “Charles always says yes.” When the gleaming new Revcon first appeared, Kuralt asked Izzy, “What do you think?”

“I think every moving part is going to break down,” Izzy replied.”We bought it anyway,” said Kuralt.

“Every moving part broke down.”

That debacle led to the purchase of the FMC 2900R shown here, the last and most celebrated of the six On the Road buses. Kuralt’s introduction to it, however, was grim. “The first time we turned on the windshield wipers,” he says, “one of them flew off and vanished into the storm.” Nonetheless, it is this motorhome that Charles, Izzy, and Larry drove 240,000 miles. Which is nearly the distance from Earth to the moon, or, in the case of On the Road, a distance equal to the most circuitous route from Cumby, Texas, to Lookingglass, Oregon, to the Holly Shelter Swamp in North Carolina, near Kuralt’s birthplace. Interspersed were unplanned diversionary meetings with Esther Wright (“the Bird Lady of St. Petersburg”), Hunter Thompson, MarIon Brando (who said to Kuralt, “If you leave this town before I catch a fish, you scum, I will find you wherever you are and kill you with my own hands”), Pete Seeger, Andrew Wyeth, and Jim Rozier. Rozier rubs truck springs across wooden stakes, which somehow causes earthworms to leap into his fingers.

Apart from two CBS eyeball logos and a largish TV antenna, the exterior of the FMC is remarkable only for its grotesque trapezoidal shape and its unremitting ungainliness—it’s 8.5 feet tall and almost 30 feet long. It is powered by a 440-cubic-inch Chrysler V-8 tucked cater-cornered behind the right-rear wheels. Without Izzy Bleckman’s cameras and tripods, without Kuralt’s typewriter and on-camera wardrobe, without microphones and reflectors and hundreds of feet of extension cords, the motorhome weighs 12,500 pounds. On the road, however, ready to record the dazzlingly simple stories of mainstream America and with three Egg McMuffin–fed men aboard, the bus usually out-larded its GVW of 14,500 pounds and wreaked inestimable carnage on its 17-inch tires.

“What I remember most clearly of life on the road was shredding tires,” Bleckman recalls. “And they were sometimes hard to replace. I once called Goodyear to find a stash. The guy asked how much the bus weighed. When I told him, he went quiet for a few beats, then said slowly: ‘Do not under any circumstances drive that thing on our tires. We can’t be responsible. We don’t want to even hear what happens.'”

“We experienced four spectacular blowouts in May ’74 alone,” Kuralt recalls. “In Ohio, both rear tires blew at once. The [motorhome] descended upon its rear springs at 60 mph, sending up a rooster tail of sparks for a quarter-mile . . .”

During Car and Driver‘s stint behind the FMC 2900R’s wheel, from Chicago to Dearborn, we quickly learned that you don’t so much drive the thing as shepherd it. It wanders constantly from berm to center stripe, with six inches of free play in the sloppy Saginaw steering. Looking like Ralph Kramden perched above his bus wheel, I developed a blister on my right palm before I realized that corrections were a waste of time; the FMC usually returns to a straight-ahead tack if you are simply patient. While you’re waiting, you also learn to cope with the world’s worst throttle response, acceleration that can be measured only with a day timer, and braking so poor that the driver must be skilled at predicting events that might transpire 30 to 60 seconds in the future.

Bleckman was amused by this analysis when we arrived with his beloved FMC at the Henry Ford Museum. “I gotta tell you, from the driver’s standpoint, this was the best motorhome we ever had.” In the cockpit, Bleckman had made some modifications: he’d installed a tilt steering wheel, a “ping control” knob to retard timing “in case we got a bad load of gas or were in the mountains,” and an Edelbrock manifold-vacuum meter. The latter served as a rudimentary fuel-economy gauge. The V-8’s dismal response to a heavy foot was to swallow as much as one gallon of high-test fuel every six miles. Bleckman met a lot of gas station attendants.

Because the notion of sleeping inside any motorhome “lasted about a week,” says Kuralt, Izzy dismantled the FMC’s bunks and discarded its beds. Everything aft of the toilet became custom shelving to hold cameras, booms, generators, TV monitors, and a zillion rolls of film or videotape. Stored on end, tripods fit snugly in the tiny shower stall, which is located behind a 12-inch decal that says, “Battle Creek: Breakfast Capital of the World.” The interior of this motorhome smells like my grandfather’s wallet.

As the miles wore on, the team modified the bus at every opportunity. “The FMC was never intended for cold-weather travel, either by mice or men,” Kuralt noted. (At least one rodent still resided therein as C/D handed the keys to the Ford museum’s curator.) “We gradually insulated it, using foam pads, bits of carpeting, rags, and old underwear to caulk its many drafty seams, but the interior still feels like a wind tunnel when the bus is up to speed . . .” The winter chills extended to the engine bay, too. Near Cisco, Utah, Kuralt recorded the following conversation:

“The carburetor’ s frozen up,” lzzy said. “Where’s the ether spray?”

“We used up the ether spray,” Larry said.

“Let’s pour in some of that Drygas,” I said.

“We used that up, too,” Larry said.

“We need some alcohol,” Izzy said.

“Well, we don’t have any,” Larry said, “except the vodka .” We looked at one another. I went into the bus and came back with a quart bottle of vodka, unopened. Larry solemnly poured [it] into the gas tank. The engine started with a roar. A mile or two later . . . the bus slowed to a stop again. “There’s always the scotch,” Larry said.

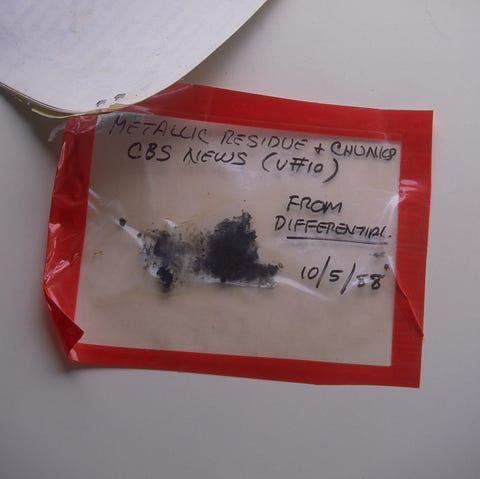

On the FMC’s last trip, there remained on board a raft of debris attesting to the motorhome’s colorful legacy of mechanical mayhem: cans of ether and “CarboChlor,” a large selection of flares, a pop riveter, a drill, fan belts, weather-strip adhesive, Liquid Wrench, an electrical schematic diagram that was obviously run over by at least one huge tire, seven unopened Champion spark plugs, a $2600 bill for a generator in Charlotte, repair bills from California alone totaling $11,749, a plastic baggie tagged with the ominous note “metallic residue and chunks from differential,” cans of Freon, a glue gun, 24 spare fuses, soldering flux, 12 lightbulbs, 100 sheetmetal screws, two complete door-latch assemblies, a snapped-off ignition key, and a thick tome titled Aqua-Magic Portable Toilet Guide.

Bleckman spent nearly as much time under the bus as in it, Kuralt recalled: “I think somewhere near Seattle, Izzy had just fixed the suspension. He drove over some railroad tracks, and it broke again. From underneath somewhere, I could hear a new sound. It wasn’t Izzy’s wrenches clanging. It was Izzy crying. The man was sobbing.” Bleckman isn’t sure exactly which time Kuralt heard the sound of his spirit snapping. “Every day, it was something else,” he says, “and not something small.”

Ironically, it was one of the myriad breakdowns that defined Kuralt’s fondest memory of 20 years on the road. “We were in Wyoming, 50 miles up a dirt road, when we had two flat tires. That was one too many. So we just sat and waited. A rancher in a pickup arrived and carried us off to fix the tires, then brought us back. Then he said, ‘Well, it’s almost dark; nothing to do but take you home with me.’ We had separate bedrooms at his ranch. We played penny-ante poker and told stories. His wife fed us elk steaks, tucked us into bed. That was the Dunlop family. We met them because the bus broke.”

The CBS trio did not videotape the Dunlop family, but it was typical of how they stumbled across stories. “More often than not,” says Bleckman, “a guy who’d seen a recent On the Road segment would just walk up and say: ‘That story was nothing. You ought to drive over and meet this guy I know who grunts worms in Sopchoppy [Florida].’ So off we’d go to Sopchoppy.”

Kuralt’s own credo for finding stories was simpler still: “Stay off the interstates.”

Evidence of the trio’s haphazard sleuthing remains in virtually every drawer inside the FMC. Among the loose business cards, we found one from “Auto Race Promotions of Saint Louis,” with a handwritten note on the back: “James Wagner, Rolla, Mo., never wears shoes.” There are others, from “Erleen G. Snow, Champion Goose Caller” and from the “Reno/Sparks Tribal Council.” One drawer contains a 12-year-old clip from the Charlotte Observer featuring Levi Fisher, the man who delivers mail to the Amish. There is a letter soliciting Kuralt to interview Allen deHart at the National Whistlers Convention, plus a program for the 1982 Thresherman’s Threshing Show.

“I’d just shoot, and Charles would follow behind, taking notes,” he explains. ‘Then later, he’d get his typewriter out, and he’d spend an hour drinking coffee, smoking, walking around. Finally, he’d sit down, and a kind of script would emerge. But you could see him agonize for an hour beforehand. It was Charlie’s routine.” For Bleckman, the most magical moments of a life spent on the road were the mornings, after the three men emerged from their “down and out” (meaning close to the parking lot) motel rooms: “We’d go out at about 7, warm up the bus. Charles would get the coffee going. We’d just sit in there and look at maps and talk. Usually, we’d just plod around inside, sometimes for an hour, drinking coffee. Then Charles would say, ‘Well, let’s go here,’ and he’d point on a map at a place about 100 miles away.”

After 20 years crisscrossing America, Kuralt can’t recall how many citizens told him he had the best, most romantic job in the world. “I always agreed I did,” he says. “But it’s funny that, in October 1967, this started as a cheap and simple three-month deal. I didn’t think of it as a great adventure. Never dreamed they’d put our bus in a museum. My plan was just to get out of the office. It worked; I haven’t had an assignment from that day to this.”

Car and Driver nursed the On the Road motorhome through its last unprepossessing hike through small-town America. We were the last to park it at the Holiday Inn in Sturgis, Michigan, where it elicited smiles among blue-haired conventioneers eating cafeteria food. And we were the last to park it in the town square of Pinckney, Michigan, where a stern woman in a flannel shirt walked up, rapped smartly on the side door, and barked, “Is Kuralt in there?” She looked like a librarian. I shouted back to her: “Charles is on the road right now. But he promised to return the book next Sunday morning.”

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

#Travels #Charles #Kuralt #Chronicled #America #Road

Source link