Illustrations by Brett AffruntiCar and Driver

From the February/March 2021 issue of Car and Driver.

There are only a couple of reasons why someone would push a Volkswagen Arteon to 120 mph. Either there is no better option for a getaway car or they’re testing it. We were testing it.

“That’ll give you an idea of the top-speed test,” said testing director Dave VanderWerp, one hand casually on the wheel. I was riding shotgun and holding a laptop wired to a Racelogic VBox 3i data logger, a five-figure piece of equipment that calculates our position and speed 100 times a second. Another wire ran from the VBox out the rear passenger’s door and up to an antenna stuck to the Arteon’s roof. That antenna connected us to seven satellites. Why do we need satellites to locate the car we’re sitting in? Because using what’s in medium Earth orbit to verify our speed and distance is more accurate than relying on what’s built into the dash. We even check the accuracy of the speedometer and odometer as part of our testing.

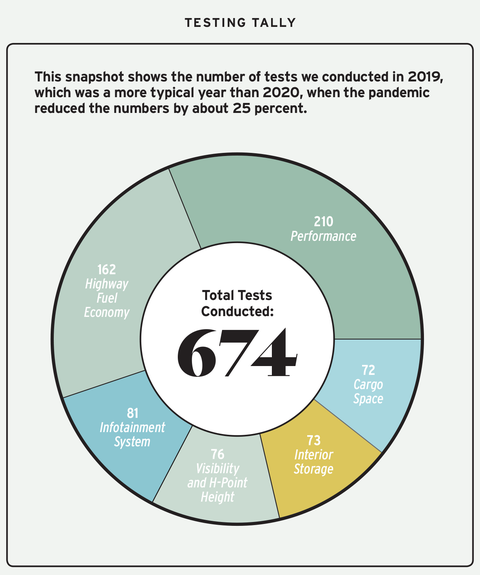

This issue is packed with numbers, and all of them fit neatly into the six-and-a-half-decade-long narrative we’ve written about how—and how well—vehicles work. We put more than 200 cars, trucks, and SUVs through the wringer each year, and we test every vehicle the same way, be it a McLaren or a Mazda, a Volkswagen or a Bugatti. It’s what makes our method scientific.

We test to keep manufacturers honest. We test to deliver facts, not just feelings, because an objective number is the best way to determine if your subjective opinion is wrong. And we test to uncover trends over time and the details that might not be revealed by a drive around town. When Toyota claimed the 2020 Supra’s center of gravity was lower than the 86’s, we measured that. Toyota was wrong.

We can tell you for a fact that Tesla’s aero wheel covers for the Model 3 improve efficiency by 2.5 percent at 70 mph, which boosts the car’s range by up to seven miles. And when Ford launched its 1999 SVT Mustang Cobra, we questioned the validity of its 320-hp claim because the car put up slower-than-expected acceleration times. Ford looked into it and, soon after our report came out, recalled the Stangs and replaced some parts so that the engines made an honest 320 horses.

Maybe you care about cargo volume in a family SUV because you have kids and kids come with a lot of stuff. We have stacks of carry-on-luggage-sized boxes we load into the back of vehicles until no more fit. Or perhaps you care more about fuel economy. We put that to the test by taking each vehicle on a 200-mile highway loop at a constant 75 mph, which is more representative of how Americans drive long distances than the EPA’s laboratory testing.

Performance testing, though, is where it all began for Car and Driver. Much of that work happens behind well-guarded gates in Chelsea, Michigan, at a 4000-acre facility owned by Stellantis (formerly Fiat Chrysler). We’ve been renters at the Chelsea Proving Grounds since the mag moved to Ann Arbor in 1978. Come with us—past CPG’s check-in desk, where we get our temperature taken and apply blue FCA-branded stickers over the cameras on our phones—as we take a peek behind the scenes and consider why it matters.

Stops

The 1.5-mile straight where we do most of our work feels a little lonely in the fading light of a crisp winter’s day. The trees are bare, the shadows long, and that piece of pavement just keeps going.

After wiring up the Arteon like it is visiting the doctor for a stress test, VanderWerp runs us up to 70 mph and then slams on the brakes. Does he do this just once? Did Sideshow Bob step on only one rake? No. We stop (a touch violently) again and again—five times fast in one direction. Then we turn around, run a length of the track to cool the brakes, and smash the pedal one more time.

No fade here: The results are all within a few feet of one another. The VW’s brakes are good, which is good to know.

Starts

Acceleration is next. Timing the run to 60 mph from a rolling 5-mph start is a C/D invention. Comparing the result with the 60-mph time reveals the extent of turbo lag, the accessibility of the engine’s power, or suboptimal gearing. Also, while there are different ways to juice the best 60-mph time from a car (e.g., brake torquing, slipping the clutch, a redline clutch dump), the 5-to-60-mph test is closer to what most people can achieve in enthusiastic real-world driving. We measure the time it takes to go from 30 to 50 mph and from 50 to 70 mph, too, because we all need to pass people sometimes. Pretty straightforward stuff—literally.

Turns

The skidpad isn’t a pad at all. It’s a circle painted on enough pavement to handle parking for half a mall. The “skid” part is accurate. Those marks are everywhere. At CPG, that circle is 300 feet in diameter, or the length of a football field, goal line to goal line. It doesn’t look that big from the car, though, and it doesn’t feel that big when you’re accelerating into the one continuous turn, tires screaming. In fact, it doesn’t feel much larger than the old playground merry-go-round. Remember that? You wanted to stay on the ride, but physics (and that friend spinning you faster and faster, laughing harder and harder) was working to pull you off. That’s the skidpad. What does the Arteon’s 0.90-g result mean? That it could exceed a 600-foot-diameter highway cloverleaf’s recommended speed of 35 mph by about 30 mph before you’d end up in the weeds. The grippiest car we tested last year, a Ford Mustang Shelby GT350R, circled the skidpad at 1.11 g’s and could take that same cloverleaf turn 7 mph faster than the VW.

The Oval

We find a little traffic on Chelsea’s 4.7-mile oval, which has banked curves at either end. This is where we ran our long-term Model 3 when we tested the aero wheel covers. VanderWerp steers the Arteon up to the top of the banking and we coast along at an effortless 100 mph in a car that’s just fine. A lot of cars are just fine, but one thing we’ve learned over time is that “fine” gets better.

Most people who buy an Arteon won’t push it anywhere near its limits. They won’t slam on the brakes five times in a mile and a half, and if they do, they might want to reconsider, well, a lot of things. But especially how they’re driving. And where.

But those spec panels we print—for good cars, bad cars, and perfectly fine cars—tell you how these machines can perform when you need a quick boost of power or have to take evasive maneuvers. Not because the automaker told you what they can do but because experts with no skin in the game put in the work.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

Source link